Featured here are articles that our writers from WIIS McGill’s Publications Portfolio have written on a wide array of issues pertaining to International Security.

Climate Conflicts: Proliferation of Armed Conflict and Increasing Climate Governance of Armed Non-State Actors

Written by: Jocelyne Guy

Edited by: Bérénice Louveau

April 18th, 2025

Peacekeepers and children wade in water after floods displace thousands in South Sudan (Andreea Campeanu)

2024 was recorded as the hottest year ever, and 2025 is 99% likely to break those records. Global Climate change has officially surpassed the political threshold established by the Paris climate treaty of limiting warming to 1.5 C. In 2024, most days of the year globally averaged 1.6 degrees above pre-industrial temperatures. While 1.5 C could still be technically feasible, experts say this is no longer a political possibility. Reducing long-term global temperature averages would require lowering global carbon emissions immediately. Still, fossil fuel production and carbon emission numbers are expected to increase exponentially at a business-as-usual pace.

Facing potential economic and ecological collapse, the implications of an above 1.5C and warming world on international security are plentiful, and all roads lead to more conflict. Hotter temperatures alone can increase interpersonal and armed conflict, but the combined impacts on the environment and ecosystems magnify damage and even total collapse of human systems we rely on for our livelihoods and well-being. So, climate change mostly increases conflict through indirect pathways. Food system destabilization will rapidly intensify due to incremental warming through heat waves that kill crops, floods that destroy food supply, and droughts that render entire regions agriculturally barren. Essential resource scarcity over food and water will worsen living conditions for millions, spark mass migration, and increase civil and regional conflict. Climate change’s exacerbation and rising frequency of extreme weather events also cause damage to food systems and livelihoods and cause mass refugee crises and conflict. The Climate-Conflict matrix then becomes a vicious cycle, where conflict increases vulnerability to climate impacts, and climate impacts increase the probability and severity of conflict.

Armed conflicts will likely explode in the coming decades without immediate and meaningful reductions in emissions as CO2 in the atmosphere continues to warm up the earth at accelerating rates. Armed conflicts are already rising globally, entering the World Economic Forum’s top 5 security risks for humanity projection for 2025. In 2024, one in seven humans was exposed to armed conflict. Climate disasters and the effects of climate change are already responsible for magnifying, prolonging, and causing active armed conflicts such as South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. These countries find themselves in regions predisposed to be more severely impacted by climate change, intersecting with their availability of critical minerals for renewable energies.

During armed conflict, armed non-state actors become central actors in local governance and crisis management to maintain control, protect economic sources, and boost legitimacy. Armed rebel groups are detrimental to the environment for many reasons, including the exploitation of natural resources and environmental destruction associated with war. However, climate impacts are increasingly forcing Armed non-state actors to engage in climate governance, mitigation, and adaptation efforts as concerns creep into the operation capacity of insurgents. As climate crises worsen, even armed rebel authorities are cornered to find solutions and partake in climate efforts to proactively fight the consequences and causes of climate change. The Polisario Front, an armed civil resistance movement of the Indigenous Sahrawi peoples in Morocco, has, for example, voluntarily produced a Climate action plan equal to those submitted by countries under the Paris Agreement. Furthermore, Somaliland, a separatist armed non-state authority, has increasingly partnered with international aid organizations and environmental NGOs to improve conservation and climate impacts.

Climate change’s impacts on global security are already showing devastating impacts, such as the proliferation of armed conflicts. In response, armed rebel groups facing climate consequences are adapting and implementing climate policies. However, this front-line response to climate impacts is more of a matter of survival and is unlikely to help impacted regions escape the Climate-Conflict trap.

Trump’s First Congressional Addressment of his Second Term and his Greenland Project

Written by: Abigail Francis

Edited by: Iona Riga

April 18th, 2025

Photo Credit: Getty Images and Trump White House Archived under public domain

Trump’s joint address to a rowdy Congress on March 4th contained a plethora of policy issues he plans to implement during his second term, stating his administration was “just getting started” and planned to make the American Dream “unstoppable”. His speech, which was one of the longest to lawmakers on record, backed billionaire turned-department head Elon Musk’s plan of slashing government funds, ridiculed Biden’s previous term and promised the resolution of the Russo-Ukraine war. Additionally, foreshadowing a second term of great power politics, he discussed an acquisition of Greenland as part of his expansionist policies (along with the Panama Canal). During Trump’s first term, he hinted at his desire to buy Greenland, the largest island in the world, although it was not “ No1 on the burner”. In this second term, on the other hand, Trump seems to be putting Greenland near the top of his list.

Greenland, home to around 56,000 residents, is an autonomous territory of Denmark, home to both Danish and US military bases and strategically positioned between the US and Europe. The island was originally governed as an isolated, relatively poor colony of Denmark for more than 250 years. However, in 1979, Greenland’s citizens voted for home rule, giving Greenland control of most of its home policies besides foreign affairs and defense to Denmark. Although much of Greenland’s economy relies on fishing, in recent years, due to climate change and melting ice, Greenland’s highly sought after natural resources such as zinc, iron, and gold as well as enormous fossil fuel reserves have become an international investment focal point.

During his speech to Congress, Trump explained that securing control of Greenland was crucial for global influence, military strategy, and national security. Trump had a strong message [for] the people of Greenland: the future is in their hands, and, if they chose to join forces with the states, Trump would “welcome them into the United States of America”. Then, with a pause and a nod, he added, “we will make you rich.” Trump has adopted a harsher tone in his second term and has suggested he wouldn’t rule out the use of force, stating that Greenland would be acquired “one way or another.” However, the majority of the residents of Greenland are not too thrilled about this possibility. The morning after the speech, Greenland’s Prime Minister Múte Bourup Egede took to social media telling Trump “Greenland is ours”, explaining the island is “not for sale and cannot simply be taken”. He concluded by saying “our future will be decided by us in Greenland”. Anne-Katrine Nielsen, a senior assistant at Greenland’s police force added that Trump does not care for the people but instead wants Greeland for their mines and location in the world.

So, why does Trump want to obtain such a remote Arctic island? It comes down to resources and military location. International interest in the Arctic has been growing, as a race between the US, China and Russia emerges for the installation of military bases, and the acquisition of resources and shipping routes. Russia has begun building its Arctic military capabilities in recent years by constructing a robust military presence with nuclear powered icebreakers and missile systems. Greenland holds a specific and strategic position on the earth. Marc Jacobsen, an associate professor at the Royal Danish Defence College notes that “if Russia were to send missiles towards the US, the shortest route for nuclear weapons would be via the North Pole and Greenland.” Furthermore, Greenland holds a vast amount of untapped resources, rich in rare earth minerals such as uranium and iron, vital to tech companies and other industries. As a result, Greenland has attracted increasing competition from China, which in 2018, laid out its China Arctic Strategy, declaring the country will play a pivotal role in the arctic resource race. Lastly, a priority for all three countries, a shipping route between Greenland and the Arctic archipelagos has begun to open due to melting ice. Soon, with these routes, transport time between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans will be faster in Arctic transportation corridors when compared to using the Suez and Panama Canals.

During the Cold War, the Arctic was a critical zone for both the U.S. and the Soviet Union, serving as a site for nuclear deterrence and military positioning. The proximity of Greenland to both North America and Europe made it a significant location for the deployment of military bases, particularly Thule Air Base, which played a vital role in early warning missile systems and strategic defense against potential Soviet attacks.

But will history repeat itself? Just as the Cold War turned the Arctic into a proxy battleground for military confrontation, today’s geopolitical struggle over the Arctic could escalate tensions between the US, China, and Russia. Although the US completely controlling Greenland seems unlikely, the military buildup in the region, as well as the race to control resources and trade routes, bears striking similarities to the strategic maneuvers during the Cold War. With global powers once again focused on the Arctic’s military and economic potential, there is concern that competition in the region could spiral into a new sort of Cold War.

Leave a Reply

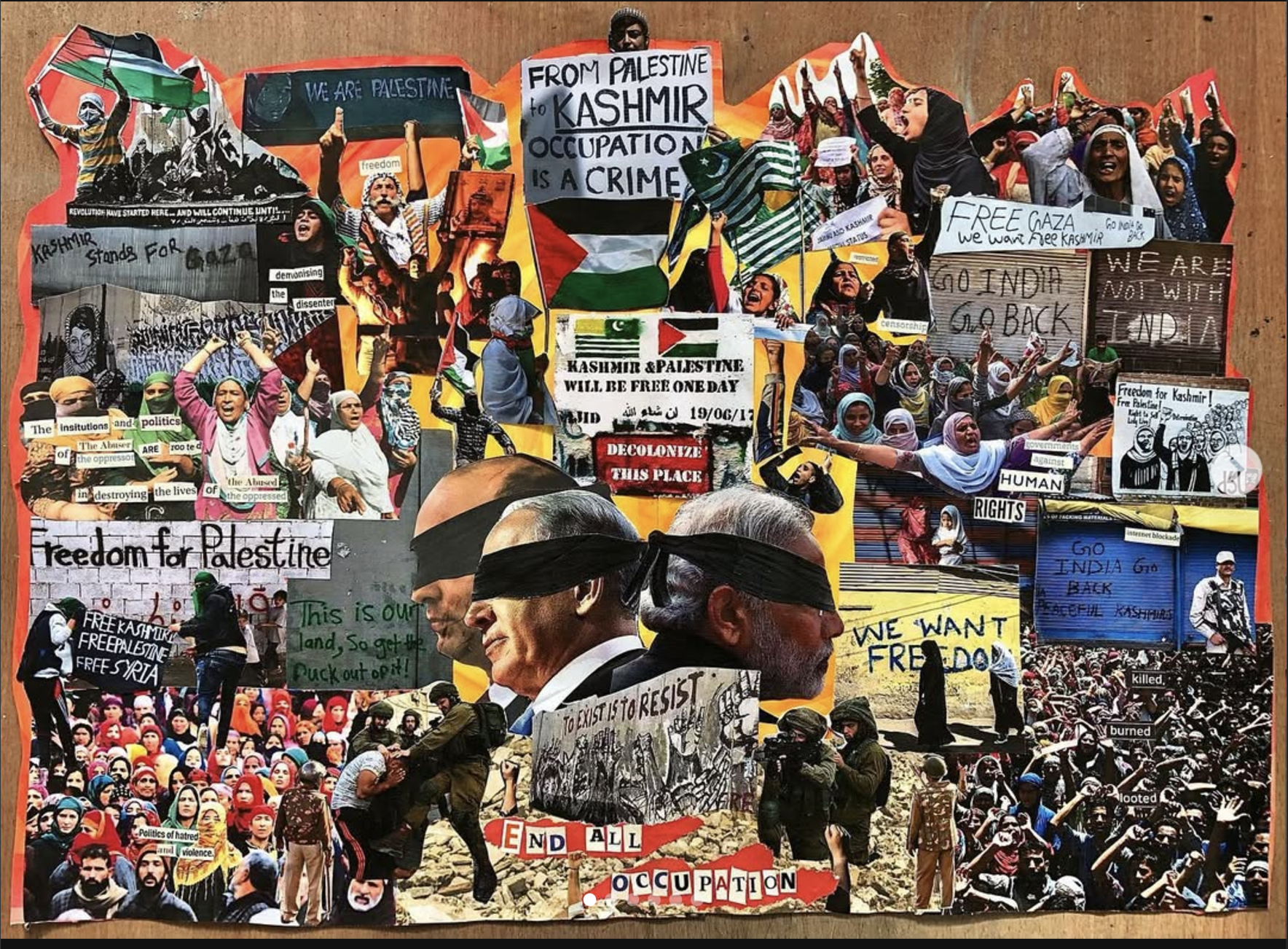

Egypt’s Plan to Rebuild Gaza: A Successful Alternative to Trump Gaza?

Written by: Meline Tarpinyan

Edited by: Gabrielle Adams

April 7th, 2025

Before Israel shattered the ceasefire agreement in Gaza on March 18, a coalition of Arab countries endorsed an alternative plan to the shocking “Trump Gaza,” in response to the President’s call to “take over” the strip and forcibly exile two million Palestinians to neighboring Arab countries. On March 4th, leaders from the Arab League attended a summit in Cairo, where they unanimously adopted the Egyptian proposal to rebuild Gaza as an alternative to Trump and Israel’s plan to forcibly displace Palestinians from Gaza. The “Arab Plan” would be carried out in three phases. First, providing immediate relief for the ongoing humanitarian crisis. Second, rebuilding destroyed infrastructure. Third, establishing a transitional governance plan in which a committee of Palestinian technocrats administers Gaza for six months before the Palestinian Authority assumes control, replacing Hamas.

Both the United States and Israel have rejected this plan, claiming Hamas must first release all Israeli hostages before it can consider – as the Arab Plan would have it – renewing the ceasefire or allowing aid into Gaza. Furthermore, the White House National Security Council spokesman, Brian Hughes, claimed the Arab Plan does “not address the reality that Gaza is currently uninhabitable.” Conversely, Israel’s foreign minister asserts that Trump’s plan for Gaza is founded on the principles of free will and the right of Gazans to escape their dire circumstances. This perspective, however, overlooks the fact that Trump’s plan grossly violates international law and does not ensure that Gazans have the right to return to, and live in, their homeland and determine the circumstances under which they wish to do so. On the other hand, Hamas has welcomed the plan but it remains unclear whether or not the group will step aside to let the Palestinian Authority take its place.

Despite the backlash from the US and Israel, Arab states continue negotiations as they attempt to partner with the World Bank to create a “trust fund” which would draw from regional and international donors such as the Gulf States to fund the $53 billion (USD) plan. The Arab Plan outlines a strategic framework for Egypt and its neighboring countries to avoid accepting millions of Palestinian refugees, who have historically faced resistance. Its architects have deliberately positioned the plan as a rational alternative to secure international support. Every element, from its three-step process to its funding sources, is designed to be marketable and adaptable for global stakeholders.

As Netanyahu, supported by Trump and other world governments, attempts to deliver on his threats to clean out the territory and displace its entire population, Egypt and Jordan are being put in a position where they have no choice but to find a viable alternative to the intake of two million refugees. However, despite the plan being dubbed as “realistic” by actors such as the EU, it was swiftly rejected by Israel and the US and followed by a renewal of violence in the Gaza strip. While the plan was a hopeful attempt to change the course of events, the war has since continued and most Arab states and other important actors have done no more than release statements calling for peace while the devastation continues. Nonetheless, as of March 24, Egypt has presented a new ceasefire proposal, hoping to end the violence that harms Palestinians and its neighboring states alike.

Leave a Reply

From Combat to Community Leadership: Ukrainian Women Defying War on Both Frontlines

Written by: Zoe Leousis

Edited by: Rebecca Larsson Zinger

April 10th, 2025

Tetiana Medvedenko (left) and Iryna Ostanko (right), both underground machine operators, walk to the elevators that will take them below the surface into a DTEK coal mine near Ternivka, Ukraine. Credit: Michael Robinson Chávez for NPR. https://www.kuow.org/stories/in-a-workforce-transformed-by-war-ukrainian-women-are-now-working-in-coal-mines

In times of global conflict, societal roles are often challenged. The erosion of gendered expectations for women during wartime is not a new phenomenon, however after Russia’s 2022 invasion, Ukraine has witnessed a striking increase in the involvement of women not only in combat but also in leadership roles and key industries such as business and mining. Defying the restrictive stereotypes that “a woman’s place is in the home” and “women are better off not engaging in physically straining, male-dominated fields,” Ukrainian women have stepped in to fill the shoes left behind by the men who have been conscripted into fighting.

While the circumstances of increasing Ukrainian gender equality are unfortunate and unavoidable, the shift in roles presents a remarkable transformation within Ukrainian society. Prior to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Soviet-era labor laws existed which prohibited women from working in harmful and dangerous situations, including over 450 professions which were considered as ‘damaging to women’s health.’ Women could not drive trains or long-haul buses, fight fires, or mine coal, and were even restricted from lifting more than 7-10 kg in the workplace (which is roughly the weight of a full-grown French Bulldog!). These policies reflected a belief that women were physically weaker and needed protection from hazardous work environments, primarily due to concerns about their reproductive health. While Ukrainian women have long been integral to the economy, their roles were historically confined to domestic spheres or industries traditionally dominated by women.

Currently, the situation is different. As a consequence of the majority of able-bodied men being forced to the front lines or losing their lives in combat, women have stepped in to fill labor gaps, supporting themselves financially and helping to keep the Ukrainian economy afloat. According to the Economy Minister, Yulia Svyrydenko “of the 36,000 small- and medium-sized companies registered in Ukraine in 2023, 51% were run by women.” In the natural energy sector, to make up for staff shortages, mines that previously never allowed women to work underground are now employing them by the hundreds. Ukrainian women are also a growing presence within private and public defense companies, making up 38% of the workforce at Ukroboronprom, the largest arms manufacturer in Ukraine. Without women in these fields, Ukrainian infrastructure would have faced even more significant challenges during the ongoing war.

Women have also volunteered to serve on the front lines, taking on combat roles alongside their male counterparts. After the beginning of Russia’s war against Ukraine in 2014, more than 62,000 women have joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine, and over 70% of them hold military positions. This rising role for women is resulting in what Dr. Oksana Kis, Cornerstones Visiting Chair in History at the University of Richmond, calls a hybrid femininity—one that “does not deny traditional femininity,” but transforms it to include “the ability to commit radical acts of resistance and participate in the active defense of what women believe is worthwhile.” This, in turn, serves as a powerful form of defiance against the Russian invasion. Women are not only contributing to the defense of their nation but also challenging entrenched patriarchal structures that have historically restricted their roles and opportunities. They are doing so without compromising their womanhood, instead redefining strength and courage in ways that challenge constrictive gender norms and pave the way for a more equitable society.

It is damning that it takes war, loss of life, and the breakdown of Ukrainian civilian infrastructure for women to be allowed into these roles. This article in no way seeks to endorse conflict as the sole means of progress, nor frame women’s advancement as an entirely positive consequence of tragedy. The hope is that these advancements are not temporary, that they will spark lasting change even long after the war is over, creating a society where women’s involvement is seen as integral to all aspects of the workforce, and gender equality is a central tenet, not just a matter of necessity.

Leave a Reply

Nigeria’s Silent War: The Surge in Gender-Based Violence and its Realities

Written by: Mara Matilda Munteanu

Edited by: Bérénice Louveau

April 10th, 2025

Protesters hold placards and banners outside the Nigerian Police Headquarters in Abuja during a demonstration to raise awareness of the recent spate of gender-based violence across the country on June 5, 2020. (KOLA SULAIMON/AFP via Getty Images)

The West African country of Nigeria is currently facing a silent war, one that is not as often portrayed in mainstream media as political turmoils or economic crises but nonetheless claims victims daily. Gender-based violence (GBV) has surged dramatically in recent years, increasing by 204% last January.. Gender-based violence in Nigeria is rooted in patriarchal values, economic hardships, and institutional failures. Despite increased awareness and activism, the realities of GBV remain dark for millions of Nigerian women.

Gender-based violence manifests in different forms, such as rape, domestic abuse, child marriage, female genitalia mutilation (FGM), and human trafficking. The 2018 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey found that 31% of women between 15 and 49 years have experienced physical violence, and 9% have experienced sexual violence. Tragically, 55% of women who have experienced physical or sexual violence have never sought help due to the widespread fear that stems from the stigmatization of GBV, as well as the lack of receptivity towards those who report abuse. A direct result of the surge of GBV in Nigeria occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, where victims were confined with their abusers for longer periods, limiting access to support services and the outside world. But GBV is not limited to the private sphere, reports of gang sexual violence and assaults in schools illustrate the widespread of GBV in Nigeria. According to UNICEF reports, with approximately 20 million survivors, Nigeria accounts for 10% of the global 200 million survivors and has the third highest prevalence of FGM.

The persistence of GBV and FGM in Nigeria is largely due to deep-rooted gender norms and cultural practices that devalue women and girls. More than 60% of women in Nigeria do not make autonomous decisions regarding their sexual and reproductive health, and 39.8% of women between the ages of 18 and 22 are forced into marriage before the legal age of 18. These ongoing realities further exacerbate women’s vulnerability to GBV, FGM, child marriages, and exploitations. Oftentimes, abuse is dismissed as a “family issue” that shouldn’t be addressed outside the home, thus preventing many survivors from seeking help or justice. Toxic religious and traditional institutions that sometimes reinforce harmful gender norms contribute to the persistence of GBV and FGM in the country. In some of these cases, sexual inequalities prevail, and women are forced to remain silent in order to protect the family’s honor.

Even though Nigeria has made legislative advances, like the 2015 Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act (VAPP) and the Child Rights Act, enforcement and compliance remain weak. Thousands of GBV violence cases are unreported in Nigeria due to fear of retaliation, shame, and the lack of trust in law enforcement. In 2020, a national dashboard was established as part of a collaboration between the EU-UN Spotlight Initiative in order to track and tackle gender-based violence in Nigeria. Just within the first three years, local reports had captured 27,698 cases of gender-based violence, but it remains unclear how many cases were left undisclosed and how many perpetrators were actually prosecuted and held accountable. Gender-based violence and discrimination based on sex happen at an alarming rate in Nigeria. In recent weeks, Nigerian female senator Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan was suspended for six months after submitting a petition in which she stated that Senate President Godswill Akpabio had sexually harassed her. The Senate President denied all accusations. Following a recent interview, Akpoti-Uduaghan stated: “The Nigerian Senate operates like a cult. The Senate president runs the Senate like a dictator, not a democrat. There is no freedom of speech, there is no freedom of expression and anyone who dares to go against him gets cut to size.” Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan has also mentioned that the Senate President had made several inappropriate gestures and comments, one of them being: “Natasha your husband is really enjoying, it looks like you’ll be able to make good movements with your waist.” Despite the heavy emotional toll, Akpoti-Uduaghan claims that she does not regret speaking up and feels that there is a need to discuss such matters and states: “[…]This is my story and my story is that of many women in Nigeria that do not have the courage to speak up.”

In order to move forward with GBV in Nigeria, a multifaceted approach is required. Strengthening laws, ensuring compliance, improving survivor support systems, and continuing to advocate and raise awareness concerning the realities and tragic effects of GBV are crucial steps in combating such abuses. Since GBV takes forms in different faucets, political will is necessary for advancement. Government institutions must recognize that GBV is an issue in Nigeria and treat it with seriousness and respect in order to make improvements. Nigeria’s silent war against women and girls must no longer be ignored, and it is now the time for action, so that every woman and girl in Nigeria can live free from violence and fear.

Leave a Reply

Memory and Power in International Relations: Australia in Timor-Leste

Written by: Annabelle Zehner

Edited by: Lynn Hoffmeister

April 3rd, 2025

An Australian soldier shakes hands with a Timorese child in 1999. Photograph: Defence Australia

Less than a quarter of a century ago, on May 20th 2002, Timor-Leste (formerly East Timor) officially secured its independence from oppressive Indonesian occupation, and became the newest member state of the United Nations. The Australian government has long cast itself as the hero of this story, attributing the success of Timorese independence to the International Force East Timor (INTERFET), a multinational non-UN peacemaking task force, organised and led by Australia.

INTERFET intervened in Timor-Leste when a humanitarian crisis emerged in the aftermath of the August 1999 UN-sponsored referendum, in which 78.5% of the Timorese population voted in support of independence. Pro-integration militia groups backed by the Indonesian military carried out a ‘scorched earth’ operation, leaving thousands of civilians dead and displacing more, and destroying the majority of infrastructure in the capital city of Dili. In just over a month – operating from September 20th until October 31st – INTERFET ensured the removal of all Indonesian troops from Timor-Leste.

For the next two years, the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) managed the nation until control was handed over to the state upon independence in 2002. This is the cut-and-dried history of Timorese independence that makes Australia look good. And yet, when historians dig a little deeper, Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) attempts to censor them.

The Australian government commissioned an official military history of Australia’s involvement in Timor-Leste in 2015. The appointed historian, Professor Craig Stockings, was granted unrestricted access to classified government records and not asked to follow any government line. The first volume, titled Born of Fire and Ash, was published at the end of 2022 after the approval process took three years (as opposed to the standard six months). DFAT gets a role in vetting such works to ensure that no classified information is featured or presents a threat to the nation.

Where is the line between a legitimate national threat and an unfavourable portrayal? While DFAT spent three years challenging Born of Fire and Ash, Stockings argued that “we can’t compromise historical integrity for convenience’s sake”. The book disrupts the conventional portrayal of Australia as Timor-Leste’s saviour. Rather, it interrogates the fact that Australia spent more than two decades determined to avoid Timorese independence to appease Indonesia and maintain control over oil resources in the Timor Gap. Thus, Australia provided cover for Indonesia’s genocidal behaviour before changing its foreign policy dramatically in the face of the 1999 humanitarian crisis and domestic public outcry.

The second volume of the official military history has already been under review for three years, with no release date in sight. DFAT does not want the Australian bugging of a Timorese cabinet room included in the telling of the 2004 negotiations over Timor Gap oil resources. Public memory influences power. The cut-and-dried history of Australia as Timor-Leste’s liberator increases the state’s legitimacy at home and abroad as a champion of the liberal international order. In that history, Australia protects self-determination and human rights as pillars of the international system. But in Born of Fire and Ash, in pursuit of its economic goals above all else, Australia is complicit in genocide, ultimately securing Timorese independence only when confronted with immense international and domestic pressure.

DFAT has stated that “while based on official documents, the views portrayed in the volumes are the views of the author, not the Australian government […] Australia has strong defence partnerships with Indonesia and Timor-Leste, which we are committed to deepening further”. Evidently, DFAT fears that Australia will lose its position in the Asia-Pacific region by rehashing old sources of tension. But the greater threat lies in the suppression of the truth. Genuine peace requires a complete understanding of the past, enabling the achievement of justice and reconciliation. Australia cannot credibly claim to be a liberal democracy while censoring its past in favour of military myths. Perhaps power comes not from a perfect record, but a willingness to admit mistakes.

Leave a Reply

America First, Aid Last: USAID Cuts Leave Millions in Jeopardy

Written by: Maya McKay

Edited by: Iona Riga

April 3rd, 2025

Source: https://www.rte.ie/news/ireland/2025/0208/1495566-irish-ngos-usaid/

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) was established in 1961 by President John F. Kennedy during the Cold War to counter Soviet influence abroad. As a pillar of US soft power, it has provided humanitarian aid, strengthened global development efforts, and fostered goodwill toward the U.S. The agency has played a key role in eradicating diseases like smallpox and polio, and constitutes the development pillar of the U.S. government’s 3D strategy: diplomacy, development, and defense. Despite its global reach – disbursing nearly $40 billion across 160 countries – it accounts for less than 1% of the U.S. GDP.

Under the Trump administration’s ‘America First’ policy, U.S. foreign aid has faced drastic cuts. On his first day in office, Trump issued an executive order freezing 90% of U.S. foreign development assistance and calling for a full review of aid programs. Nearly all of USAID’s 10,000 global staff were dismissed. While some life-saving programs received waivers, most did not, leaving USAID officials scrambling for exemptions while facing threats from the newly created ‘government efficiency agency’ headed by U.S. billionaire Elon Musk. The consequences were immediate.

Described as an earthquake across the aid sector, programmes including those providing medication to the world’s poorest and installing clean water supplies had to stop overnight. In Syria, for example, the White Helmets, renowned for their life-saving efforts in weapons management- were forced to halt operations, raising concerns about unchecked chemical weapon proliferation. In 2024 alone, nearly 16 million Ethiopians relied on donated grain, with USAID as the largest supplier through the UN World Programme. As Global Citizen warns, the human cost of freezing US foreign aid is undeniable.

Beyond the humanitarian toll there are major strategic risks of cutting foreign aid. These cuts undermine U.S. soft power, weaken global partnerships, and cede influence to rivals like China and Russia. It poses a fundamental question; Is Trump undermining the U.S.’s own interests?

Halting aid not only weakens global stability, it also risks backfiring on American hegemony. Could this be a calculated strategy to keep weak states weak, or an attempt to consolidate hegemony by exploiting instability? Critically, such cuts create power vacuums that the U.S. can not afford. If Washington withdrawals from funding humanitarian crises and adversaries like Russia step in, the result is a direct erosion of U.S influence, the worry USAID was established to address. Moreover, reduced aid opens the door for extremist groups to exploit vulnerable populations, further destabilizing already fragile regions. In short, freezing international aid does not just abandon those in need – it comprises global security and weakens U.S. strategic power.

Leave a Reply

A Renewable Future or Just a New Era of Resource Exploitation? How the Green Gold Rush is Reshaping Geopolitics, Supply Chains, and Global Power Dynamics

Written by: Adrienne Calzada

Edited by: Rebecca Larsson Zinger

March 27th, 2025

Photo Credit: David de la Iglesia Villar

With human activity permanently altering the Earth’s climate, further pushing the planet toward an environmental crisis characterized by rising temperatures, extreme weather, and ecosystem collapse, it is indisputable that a fundamental shift in our energy and consumption patterns is required. Decades of reliance on fossil fuels have created a dangerous cycle of carbon lock-in, where investments in high-carbon infrastructure and technologies create a self-reinforcing cycle, making it increasingly difficult and costly to transition to low-carbon alternatives, thereby hindering climate action. According to IRENA’s 1.5°C scenario, however, electricity is projected to become the primary energy carrier in the future, with its share more than doubling from 22% today to 51% by 2050. Furthermore, biomass and hydrogen are expected to constitute more significant portions of the total energy consumption than fossil fuels. The shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy thus fosters the development of electrified, decentralized, and digitalized energy systems. These renewable-based systems, including green hydrogen and sustainable biomass, are inherently more efficient and support higher rates of electrification, enhancing overall energy sustainability.

This impending energy shift is fuelling a new resource scramble—not for oil, but for the critical minerals that power clean energy technologies. The transition from fossil fuels to renewables is driving global demand for lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements, essential for batteries, EVs, and solar panels. The race to decarbonize the global economy is thus introducing a Green Gold Rush, where countries compete to secure access to these scarce resources, reshaping global trade patterns and geopolitical alliances. Unlike fossil fuels (which are more geographically widespread), critical minerals are concentrated in only a handful of countries, making supply chains vulnerable to political instability, resource nationalism, and market volatility. This reliance on a few key suppliers raises concerns about supply security, ethical mining practices, and environmental sustainability.

As nations race to control these essential materials, new power dynamics are emerging that could redefine global trade, strategic alliances, and economic dependencies. This shift also exposes the unequal distribution of costs and benefits in the clean energy transition, as resource-rich developing nations often bear the environmental and social consequences of extraction while wealthier nations reap the benefits of decarbonization. The question remains: Will this new energy order be more equitable than the fossil fuel era, or will it replicate the same patterns of exploitation and conflict?

First, What Will a Green Energy Transition Look Like?

The Green Gold Rush is occurring amid severe geopolitical tensions brought forth by the pandemic’s economic consequences, rising protectionism, and escalations of current global conflicts (i.e. Sudan, Ukraine, Gaza). Such disruptions have profoundly affected trade relationships, economic alliances, and supply chains, particularly in clean energy and mineral sectors. As countries compete for power, they increasingly vie for control over strategic resources. These tensions are further exacerbated by rising technology prices and supply vulnerabilities, which intensify concerns over foreign dependency and trade security. The attacks on the Nord Stream pipeline and disruptions in Red Sea oil and liquefied natural gas shipments, for example, illustrate the profound interconnectedness of energy security and military conflicts.

Although residual dependencies on fossil and nuclear fuels will remain, new dependencies will simultaneously emerge around increased trade in electricity, hydrogen, critical materials, and clean technologies. These new dependencies are remarkably different from conventional and precedented fossil fuels dependencies, however. The current geopolitical environment raises concerns regarding foreign dependency and alters partnerships and alliances. Moreover, these new dependencies will comprise highly concentrated supply chains, posing serious risks as they create economic instability, geopolitical conflicts, and environmental and ethical concerns. As demand for critical minerals skyrockets, addressing these vulnerabilities will be essential for a secure and just energy transition. For example, the European Union’s accelerated pivot away from Russian natural gas following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine led to urgent investment in alternative energy sources and infrastructure. This sudden shift revealed how existing energy ties can be disrupted by conflict, prompting countries to reassess their energy security strategies and scramble for access to new technologies and materials.

The Lithium Triangle and the Democratic Republic of Congo: Geopolitical Leverage, Supply Chain Vulnerabilities, and Resource Nationalism

Lithium and cobalt are essential to the energy transition as the world shifts away from fossil fuels, reshaping economic relationships and dependencies. Unlike oil, which is found in multiple regions, these critical minerals are heavily concentrated in a few countries, giving them new leverage over global energy markets. The Lithium Triangle (Argentina, Bolivia, Chile) holds over 50% of the world’s lithium reserves, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) supplies 70% of the world’s cobalt, essential for EV batteries, solar panels and wind turbines. Consequently, these mineral-rich nations may gain greater geopolitical leverage, influencing global energy markets as demand for critical materials surges. Meanwhile, oil-rich nations—particularly those with established economic and political power like Canada and Saudi Arabia—are unlikely to see their influence disappear but will need to redefine their strategies to maintain their geopolitical relevance in an energy landscape increasingly shaped by renewables and resource diversification.

Resource dependency on a few key suppliers raises supply chain vulnerabilities, ethical concerns, and environmental risks. Lithium extraction is water-intensive and strains arid regions like Chile’s Atacama Desert, exacerbating pre-existing tensions with Indigenous communities over land degradation. Additionally, cobalt mining in the DRC has been linked to child labour, corruption, and hazardous conditions, intensifying calls for ethical sourcing and supply chain transparency. A transition to greener energy sources, therefore, risks the legitimization of, encouragement and complicity in unethical resource extraction, calling for a reevaluation of what this transition indeed implies and a reassessment of how sustainability is defined- equally in terms of reducing carbon emissions and in ensuring ethical, equitable, and environmentally responsible resource extraction practices.

Furthermore, China dominates global processing, refining 60-80% of lithium, cobalt, and other rare earth elements, similar to OPEC’s past control over oil. This consequence prompts nations to reevaluate their supply chains, with policies like friend-shoring, domestic resource investments, and trade alliances to reduce reliance on China’s refining control.

The rise of resource nationalism poses an additional threat. Governments in Chile, Bolivia, Indonesia, and the DRC are imposing stricter regulations, nationalizing mining industries, and initiating contracts to capture more economic benefits from their resources. While these efforts increase local economic control, they also create investor policy uncertainty, leading to potential market volatility and trade tensions. Furthermore, disruptions caused by natural disasters, political instability or trade disputes in those countries can result in shortages or price fluctuations, affecting global energy markets. As the competition for critical minerals intensifies, balancing national resource sovereignty with global energy security will be crucial in determining whether the Green Gold Rush fosters greater economic independence for resource-rich nations or exacerbates instability and supply chain vulnerabilities in the renewable energy era.

Is the Green Transition Just Another Exploitation Cycle?: Colonial Déjà Vu in Energy Politics

The clean energy transition is promoted as a solution to the climate crisis; however, it also exacerbates global inequalities, disproportionately benefiting wealthier nations while placing the burden on resource-rich but economically vulnerable countries. This dynamic, often described as green colonialism, mirrors historical patterns of exploitation, where raw materials are extracted from the Global South to fuel development in the Global North.

The Global North’s control over supply chains and trade policies has reinforced economic dependency, preventing resource-rich nations from fully benefiting from their own natural wealth. Additionally, the Green Gold Rush raises critical questions of energy equity—how can wealthy nations justify blocking fossil fuel investments in developing countries while continuing their own fossil fuel production? By limiting economic growth opportunities in the Global South, the Global North risks ensuring that the clean energy transition replicates the same structural inequalities and dependencies that defined the fossil fuel era.

Despite its promise, the clean energy sector is not inherently sustainable. Lithium mining depletes water tables, exacerbating droughts in already arid regions, while nickel and cobalt extraction contributes to deforestation, biodiversity loss, and toxic pollution. Additionally, large-scale mineral extraction efforts often disregard Indigenous land rights and fuel social unrest, as local communities bear the environmental and health costs without receiving the economic benefits.

This extractive logic is not limited to mineral resources. Corn-based ethanol offers a parallel example of how green energy policies can unintentionally undermine sustainability and equity. Following the implementation of NAFTA in 1994, the U.S. increased exports of heavily subsidized corn to Mexico. This influx depressed local prices and displaced small-scale Mexican farmers who could not compete with U.S. agribusiness. Corn prices surged globally as demand for ethanol grew in the early 2000s, driven by U.S. biofuel mandates and subsidies. In Mexico, this created food insecurity and social unrest as corn- central to the country’s diet and culture- became less affordable for millions. Meanwhile, ethanol’s climate benefits are increasingly contested as studies increasingly confirm that corn ethanol can generate nearly twice the greenhouse gas emissions of gasoline over a 30-year span when accounting for land-use change, fertilizer use, and processing emissions. The ethanol case illustrates how so-called green solutions can reproduce both environmental harm and economic displacement despite their intended goals of promoting sustainability

The Green Gold Rush may, therefore, provoke a feeling of colonial déjà-vu, where the pursuit of progress and industrial advancement comes at the expense of marginalized communities and fragile ecosystems, raising the question of whether the green energy revolution is truly different or simply repeating the same extractive logic in a new guise.

Decarbonization Cannot Repeat the Exploitation of the Past: True Sustainability Requires Equity and Bottom-Up Solutions

The Green Gold Rush is reshaping global trade, geopolitics, and economic power, shifting dependencies from fossil fuels to critical minerals. While the transition to renewable energy is essential for mitigating climate change, it also introduces new risks in supply chain security, environmental degradation, and global inequality. As mineral-rich nations gain strategic leverage, supply chain bottlenecks, trade disputes, and political instability could disrupt access to these essential resources, putting global energy security at risk.

Additionally, the current renewable energy model risks replicating the same exploitative structures of the fossil fuel era, in which economic growth in wealthier nations is prioritized while environmental and social costs are externalized onto developing regions. A clean energy revolution can only be successful if ethical supply chains, fair trade agreements, and investments in sustainable extraction practices are implemented, further complicating an already complex decarbonization effort. These efforts are imperative, however, as the clean energy revolution cannot come at the expense of the very people and ecosystems it seeks to protect.

The current uncertain geopolitical climate, coupled with the unprecedented nature of this transition, begs the question: Can we break from the extractive cycles of the past, or will the Green Gold Rush become the next frontier of resource exploitation? Is the clean energy transition indeed a pathway to sustainability or a new iteration of economic and environmental injustice?

Leave a Reply

The Rohingya: A Struggle for Survival and Recognition

Written by: Alice Tremblay

Edited by: Rebecca Larsson Zinger

March 27th, 2025

Rohingya refugees crossing the Bangladesh-Myanmar border. Photo Credit: Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters

Myanmar’s decades of military rule and ethnic tensions have fueled severe human rights violations against the Rohingya, a Muslim ethnic minority in the country’s Rakhine State. The Rohingya have been subjected to systemic persecution, with little protection or recourse.

Myanmar’s 1982 citizenship law in particular denies them legal recognition, essentially leaving them stateless. This legal exclusion has paved the way for widespread discrimination, including restrictions on movement, education, and employment. Tensions escalated dramatically in August 2017 when Myanmar’s military launched a brutal crackdown described by the United Nations as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” This operation in the Rakhine State led to mass killings, sexual violence, and the destruction of villages, forcing over 700,000 Rohingya to flee to neighboring Bangladesh.

The influx of refugees resulted in the establishment of overcrowded camps in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar district; notably the Kutupalong camp, which is now the world’s largest refugee settlement. The camp’s high density and limited resources pose considerable challenges to sanitation and healthcare. For basic necessities, refugees rely heavily, if not entirely, on humanitarian aid.

Within the camps, security has deteriorated due to the emergence of armed groups, such as the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army. Initially formed to resist Myanmar’s military, ARSA has been implicated in criminal activities within the camps, including abductions and killings of fellow refugees. Recent reports even indicate that ARSA’s leader, Ataullah Abu Ammar Jununi, was arrested by Bangladeshi authorities on charges related to illegal entry and terrorism.

While the international community has condemned the atrocities committed against the Rohingya, aid agencies have been facing challenges like funding shortages and restricted access to affected populations. The potential reduction in foreign aid, particularly from major donors, such as the United States, threatens to worsen the already dire conditions in the camps. Without sustained support, the prospects for improving the living conditions of the Rohingya will remain low.

Addressing the Rohingya crisis requires a coordinated international response. Legal accountability through bodies like the International Criminal Court is essential to deter future abuses. Expanding humanitarian aid is crucial to meet the immediate needs of refugees, including food, healthcare, and education. It is also vital to empower local communities to participate in the relief process to ensure that aid is both sustainable and culturally appropriate. Long-term solutions should focus on safe and voluntary repatriation when conditions allow, or alternative pathways like local integration. Ultimately, ensuring the protection and rights of the Rohingya will require both a commitment to justice and a concerted effort to address the root causes of their displacement. Regional cooperation through ASEAN and sustained global engagement are critical to promoting security, protecting human rights, and supporting lasting peace in Myanmar.

Leave a Reply

Trump, Greenland, and the Return of Imperial Dreams; Are 19th-Century Expansionist Tactics making a 21st Century Come Back?

Written by: Maya McKay

Edited by: Iona Riga

March 20th, 2025

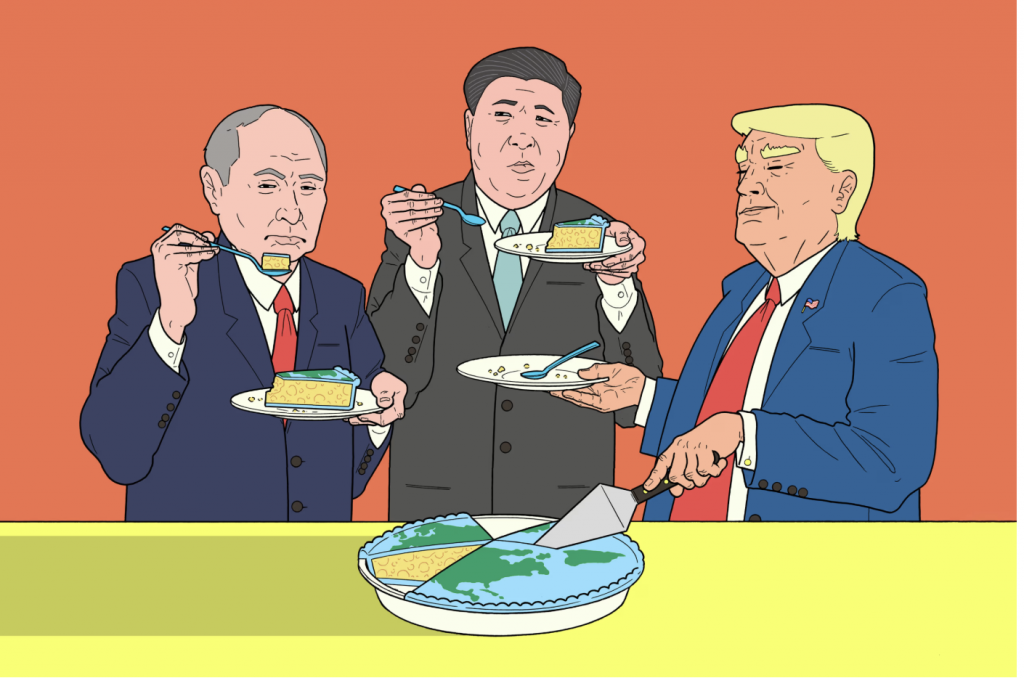

Illustration: Kyle Ellingson in “In a New Age of Empire, Great Powers Aim to Carve Up the Planet” by Yaroslav Trofimov

Skinny jeans, wired headphones, and digital cameras are all making a comeback – and if you ask the world’s most powerful leaders, so is imperialism.

Post-WWII, nations took to San Francisco to sign the UN Charter, in which they pledged to abide by international law and respect state sovereignty, regardless of a country’s size or strength. Despite this, in a new age of empire, today, great powers are imposing their will on smaller states, carving up the planet; slice by slice. Russia’s war of conquest in Ukraine rages into its third year. China escalates its military provocations against Taiwan. And now, Trump revives his audacious threat to claim Greenland.

Home to about 57,000 Inuit people, Greenland is controlled by Denmark, a NATO member. Its strategic location has long made it valuable to the U.S., which established military bases there after World War II. As Arctic tensions rise, Greenland’s proximity to potential Russian missile routes makes it a key player in defense agreements, fueling U.S. interest in the island. Additionally, climate change is creating new economic and military opportunities ripe for Trump’s taking. The melting of major ice sheets is opening new shipping routes, increasing maritimes traffic and allowing access to previously untapped natural resources. Among these resources – lithium – a critical component in electric vehicle batteries – has become particularly significant. The irony is that lithium is essential to Tesla’s production, a billion dollar company led by Elon Musk, Trump’s latest bro-mance. Plus, with China currently dominating the global lithium supply, the U.S. has a strategic interest in securing alternative sources.

With these motives in mind, Trump stated that “I’m not going to commit to [ruling out military action]. It might be that you’ll have to do something. We need Greenland for national security purposes.” And to all of this, Danish politician Anders Vistisen says ‘It is not for sale. Let me put it into words you might understand, Mr.Trump: fu*k off.’

While the prospect of the U.S. annexing Greenland remains unlikely, such threats should not be dismissed. This rhetoric reflects a broader resurgence of 19th-century-style power politics, where territorial ambitions and strategic interests override normative considerations like sovereignty and self-determination. Greenland is merely one example of powerful actors disregarding the legitimacy of nations, operating under the assumption that their ambition alone justifies action. If the post-war order was built on the promise that might would no longer make right, then the return of imperial ambitions – from Greenland, to Canada, to the Panama Canal, to most recently, the Gaza strip – suggest that that promise is unraveling. The question now is whether the world will hold the line, or if great powers will continue carving up the globe, one bold claim at a time.

Leave a Reply

The Unseen War

Gender-Based Violence in Refugee Camps: Beyond a Humanitarian Crisis, a Global Security Threat

Written by: Jeanne Belva

Edited by: Lynn Hoffmeister

March 20th, 2025

Rohingya girls pump water in Balukhali refugee camp, Bangladesh. Many of the gender equality targets are directly linked to sanitation. ©UN Women/Allison Joyce

By the end of 2024, an estimated 123 million people worldwide had been forcibly displaced due to persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations, and widespread instability. This is not just about migration—it is a global unraveling, a violent reconfiguration of international order fueled by the failures of states, institutions, and collective human empathy. Refugees are not merely seeking shelter; their movement exposes the fragility of states, the inadequacy of global governance, and the false assumptions that borders are barriers against chaos. Far from a temporary exodus, it is a seismic shift in the global security landscape.

Policies addressing forced migration often focus on its root causes—wars, persecution, or natural disasters—while failing to address the dangers that arise within the very places meant to provide refuge. Refugee camps and emergency shelters are not neutral havens. In many cases, they are incubators of new crises, where systemic neglect turns displaced individuals into targets of violence, exploitation and human right abuses. Among the most overlooked yet underreported threat is gender-based violence (GBV). Women and girls in refugee settlements face an unrelenting assault on their dignity and safety, trapped in spaces that were never designed to protect them. The conditions in these settlements – overcrowding, lack of privacy, unsafe sanitation facilities, and inadequate security – create a reality where GBV is not just a possible risk but an expectation.

Indeed, women in shelters face severe risks due to inadequate privacy, lack of gender-segregated sanitation, and systemic disempowerment. For instance, in cases of climate-induced displacement, studies show that 71% of Bangladeshi women experienced increased violence (here specifically during flood-related migrations). Reports highlight high rates of sexual violence in emergency shelters, particularly during sleep, bathing, and dressing. The lack of doors, locks, or proper lighting in many shelters forces women to suppress their basic needs until nightfall, when the risk of assault becomes even greater. For Muslim women, privacy is even more critical due to religious and cultural norms, yet survivors often remain silent due to stigma and fear of ostracization.

However, this failure to provide safe and dignified refuge is not just a humanitarian shortcoming; it is a global security threat. When the states and its institutions ignore the suffering of displaced people, we do not just fail them—we fail ourselves. We allow instability to fester, violence to spread, and resentment to grow.

The consequences of this neglect are not confined to the refugee camps. In Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh, the lack of privacy and security for women significantly increases their vulnerability to human trafficking networks. These networks exploit climate-displaced women, coercing them into forced labor, prostitution and criminal activities. The International Organization for Migration has identified young girls being sold into forced labor as the largest group of trafficking victims in these camps. Additionally, Human Rights Watch has documented cases of violence against Rohingya refugees, including murder, kidnapping, torture, rape, sexual assault, and forced marriage, highlighting the severe security challenges within the camps. In Nigeria, the extremist group Boko Haram infiltrates refugee settlements, employing sexual violence as a weapon to destabilize communities and recruit fighters. Amnesty International reports that Boko Haram fighters have subjected women and girls to rape and other forms of sexual violence during attacks in Borno State, actions that constitute war crimes.

The world has witnessed this before. The mass displacement from Syria fueled the rise of extremist groups, overwhelmed European asylum systems, and reshaped political landscapes across the West. The refugee crisis of today is the geopolitical crisis of tomorrow. Failing to secure and support displaced populations doesn’t just mean human suffering but allows breeding insecurity that will ricochet across continents.

Ensuring gender-segregated facilities, secure shelter, and protection for vulnerable populations is not charity—it is security policy. Ignoring these needs is a choice, and that choice has far reaching aftereffects: radicalization, human trafficking, geopolitical instability, and cycles of violence that will inevitably spill beyond borders.

Leave a Reply

Women in the Crossfire: The Gendered Toll of Sudan’s Humanitarian Crisis

Written by: Dena Ojaghi

Edited by: Gabrielle Adams

March 13th, 2025

Cover Photo: Sarah Dink carries her child while going to a camp in Gezira state, on Dec. 10, 2023. She says, “I’m worried about my children’s future. I am thinking of returning to Abyei so that I can provide education for my children.” Faiz Abubakr

Waging famine in Sudan has left women and children vulnerable to both severe health crises and a brutal political conflict. As Sudan’s political climate darkens, women and girls are disproportionately affected, facing higher levels of famine, violence, and death than their male counterparts. The country is experiencing it’s worst humanitarian crisis as the civil war, which began in April 2023, continues to escalate. The ongoing power struggle between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a rebel paramilitary group, is intensifying, while a massive hunger crisis reaches unprecedented levels. International relief efforts are dwindling due to delivery sanctions. Doctors Without Borders has warned that Sudan’s medical system is on the brink of collapse, exacerbated by the near-total flight of volunteer forces and escalating brutality on the ground. With the RSF controlling most aid distribution, activists and volunteers are losing hope as the group continues to block humanitarian assistance and hinder political progress. Sudan’s pro-democracy movement, initially driven by mass protests, had sparked a decentralized transition toward an elected civilian government. However, this process was deliberately obstructed when General Abdel-Fattah Burhan and RSF leaders staged a military coup in October 2022, triggering the ongoing conflict. The vast scale of the conflict is difficult to conceptualize as, despite being deemed the world’s greatest humanitarian emergency and devastating virtually every facet of Sudanese society, only 60 percent of international funding appeals are being met by the international community.

Sexual violence has now become a weapon in the context of this civil war and puts Sudanese women at an all-time vulnerable position. Framed as a “total war” on the bodies of women and girls by the United Nations Population Fund, gender-based implications of the conflict are obvious. Wielded as a weapon to terrorize communities and exert control, reports of sexual abuse have skyrocketed with the Fund having had to reach more than 112,000 women with sexual and reproductive health services in the past year alone. Sudanese activists have put out a call for more medication, medical supplies, dignity kits and post-exposure prophylaxis kits to prevent HIV transmission and to support the clinical management of rape, where timely and accessible healthcare in the face of conflict has been scarce.

Sexual abuse isn’t the only form of violence highlighting gender-based discrimination and dynamics in Sudan. In ten Sudan states, 64 percent of female-headed households are experiencing food insecurity compared to 48 percent of male-headed households: women and girls are eating least and last. Women on the brink of starvation are having to resort to drastic actions such as engaging in survival sex or forced marriage; endangering their livelihoods becomes the only source of hope for survival.

Although Sudanese women are disproportionately affected by the humanitarian crisis, their stories extend beyond these challenges, continuing as a testament to resilience and determination. Women in Sudan have risen as agents of change to neutralize and combat human rights violations. The pivotal pro-democracy movements triggered to drive President Omar al- Bashir out of office were spearheaded by female activists, like 22-year-old protester, Alaa Salah and Wifaq Quraishi, leading to the successful ousting of President Bashir who is still at large as he faces five counts of crimes against humanity.

Female activists continue to drive advocacy for a more inclusive and equitable society by mobilizing women to unite against military abuse and violence. Naama’s story is that of a Sudanese woman mobilizing her community amidst the crisis in Khartoum; Naama joined forces with other local community members to establish an organization focused on combating gender-based violence. Despite dealing with personal tragedies, Naama facilitates the collaboration of Sudanese women to provide assistance for endangered girls in the capital. Becoming an essential silent hero and an inherent part of the fire-line response in Sudan all the while providing crucial support networks for women and girls facing sexual violence and forced marriage, Naama exudes what it means to be resilient.

With over 25 million people in need of humanitarian aid, the latest United Nations Humanitarian Affairs response plan outlines that vital aid has only reached 11.7 million Sudanese civilians out of a population of more than 51 million. International assistance is nowhere near the threshold required to provide lifesaving resources to Sudanese people as the crisis reaches a crux. The United Nations continues to prioritize civilian protection in its aid efforts, yet the pressing need for conflict de-escalation and unrestricted humanitarian access across borders and conflict lines highlights the immense scope of support Sudan requires. Funding and specialized aid targeted towards women and girls in Sudan are put forth by the United Nation’s emphasis on the centrality of gendered protection, aiming to reduce further harm and destruction while simultaneously aiming to rebuild and restore the livelihoods of women and girls.

Leave a Reply

Redefining Sovereignty: the Climate Crisis in Small Island Developing States

Written by: Annabelle Zehner

Edited by: Lynn Hoffmeister

March 13th, 2025

Simon Kofe addresses COP26 from the water. Photograph: Tuvalu Foreign Ministry/Reuters

On November 9th, 2021, a video of Tuvaluan foreign minister Simon Kofe was shown at COP26, the United Nations Climate Change Conference held in Glasgow that year. In the footage, Kofe stood knee-deep in seawater, on what was once completely dry land, visually appealing to the international community that the threat of climate change is no longer distant or theoretical. Tuvalu, a Small Island Developing State (SIDS), comprises nine islands, which have a total combined land area of less than 26 km2, with the highest point above sea level at a mere 4.6m. Tuvalu’s geography and low economic development place it on the frontlines of the climate crisis, making it particularly vulnerable to rising sea levels and extreme weather events resulting from climate change, despite producing some of the lowest levels of greenhouse gas emissions in the world.

According to Westphalian tradition, enshrined under international law, sovereignty is defined as complete control within a clearly defined territory. However, as Tuvalu’s landmass is diminishing due to forces beyond its control, its existence as a sovereign state is called into question. How can Tuvalu retain its sovereignty when faced with such an existential and border-defying threat as the climate crisis? Can a state be sovereign without physical territory?

Given the border-defying nature of the climate crisis – wherein nearly every state contributes, and nearly every state will inevitably face its consequences – effective climate action can not and will not be achieved without global cooperation. And yet, the response of the international community has been hugely underwhelming considering the immediacy of the threat. Tuvalu’s population is set to become the world’s first climate refugees, a category not currently recognised or protected under the Refugee Convention. On November 10th, 2023, Australia and Tuvalu signed a treaty offering a pathway to permanent residency for up to 280 displaced Tuvaluans per year. However, former Prime Minister Enele Sopoaga has stated that this approach is “self-defeatist”, allowing the land, a site of rich cultural history, to succumb to the impacts of climate change, rather than attempting to prevent and control them. Further, Australia has been accused of striking this deal in the interest of its power competition with China in the Pacific, and not out of genuine concern for the climate.

On November 15th, 2022, Simon Kofe returned to the international stage on video at COP27 – held in Sharm el-Sheikh that year – announcing Tuvalu’s Future Now Project. In the video, Kofe stood on land that was revealed to be digitally generated, declaring that in the face of global inaction, and rapidly rising sea levels, Tuvalu had “no choice but to become the world’s first digital nation”. Tuvalu has created a digital clone of itself in the metaverse in an attempt to archive the nation’s rich history and culture, and eventually move all government functions online. The Future Now Project is a substitute for the physical, allowing the state to function and national identity to persist in the absence of land.

In line with the development of its digital clone, Tuvalu has changed its legal definition of statehood. The constitution states that “the State of Tuvalu within its historical, cultural, and legal framework shall remain in perpetuity”, meaning that its existence is not contingent on physical land. Under international law, however, this is not the case; a state must have clearly defined borders and a permanent population to be considered sovereign. Tuvalu is engaged in ongoing efforts to have its new definition of sovereignty recognised so that it may retain control over its maritime zones, international voting rights, and its voice on the world stage, even if its territory becomes fully submerged.

By presenting a new model of statehood, the case of Tuvalu draws attention to evolving conceptions of sovereignty in the face of border-defying global political challenges such as the climate crisis. However, the future of its statehood ultimately depends on whether the international community chooses to act.

Leave a Reply

The Hidden Cost of Palm Oil

Written by: Alice Tremblay

Edited by: Rebecca Larsson Zinger

March 7th, 2025

Photo of oil palm trees at a plantation in West Papua, Indonesia. Credits: Dr. Sophie Chao

Palm oil is found in almost everything, making up about 50% of packaged products in supermarkets, from pizza and doughnuts to deodorant and shampoo. While this crop is native to West Africa, 85% of its global supply today comes from Indonesia and Malaysia. Its arrival in Southeast Asia was slow and uneventful; initially brought as an ornamental tree crop in the late 1800s, it was never anticipated to be such a lucrative commodity. Overtime, however, it has brought harm to the people who call these lands home. Namely, the Indigenous Marind people of West Papua in Indonesia have seen, in a matter of two decades, a dramatic shift in their way of life. While oil palm projects were framed as essential to national interests, regional growth, and the “development” of West Papuans, the reality for the Marind people has been one of displacement, marginalization, and environmental destruction.

There has been widespread biodiversity loss, deforestation, and severe water pollution in the region since the introduction of industrial oil palm production, and these issues only worsen with its continuing harvest. As sago groves are destroyed and river ecosystems deteriorate, the Marinds’ food sources are directly threatened, forcing them to rely on imported goods and no longer their land. Employment opportunities that were also promised to the Marind remain scarce, as companies prefer to bring in their own migrants to work. Moreover, these plantations have private security forces and state-sanctioned military personnel that protect plantations, and serves to silence Indigenous resistance through intimidation, surveillance, and arrests. Indigenous activists fighting for land rights are thus often criminalized, for corporations and the Indonesian state collaborate together to continue exploiting and profiting off of this land. Such exploitation only further reduces the Marind’s ability to assert control over their own territories.

This shift has not only undermined their autonomy but also altered their perception of the land. The forest, once seen as a site of kinship between the human and the non-human, is now believed to be dominated by the invasive crop that is palm oil. Palm oil has managed to change the fabric of Marinds’ dreams, worldview, and everyday interactions, leading to a change in the meaning of the Marind identity. When traditional ways of life become untenable, cultural knowledge, oral traditions, and spiritual practices are at risk of disappearing.

The security crisis facing the Marind reflects a broader global issue, in which Indigenous communities bear the cost of resource extraction for international markets. While millions comfortably access palm oil, rivers in West Papua are polluted with agrochemical runoff and local communities suffer. Without meaningful protections for their land and rights, the Marind are left increasingly defenseless against an economic and political model that treats their homeland as expendable.

Leave a Reply

Digital Diplomacy or Digital Dispossession? Women’s Fight for Visibility

Written by: Adrienne Calzada

Edited by: Rebecca Larsson Zinger

March 6th, 2025

Photo Credit: UN Women/Catianne Tijerina

X (formerly known as Twitter) has established itself as the predominant social media platform diplomats use globally, preferred over other platforms such as Facebook, Snapchat, and Instagram. X allows diplomats and foreign ministers to engage with their audiences directly, redefining international discourse spaces and rendering the app a powerful tool with critical influence. Importantly, X and other social media platforms offer female diplomats the unprecedented opportunity to reach new audiences, engage in public diplomacy, and gain new forms of agency. Their digital influence, however, remains disproportionately limited. The digitization of diplomacy, while transforming international relations, also introduces new challenges for women. Gender bias in diplomacy is now embedded in digital platforms, shaping the visibility and influence of female ambassadors in ways that replicate traditional barriers.

Analyses of X and virtual diplomacy show that rather than levelling the playing field, digital platforms reinforce preexisting gender hierarchies in which men dominate engagement, decision-making, and visibility, as women remain underrepresented in key diplomatic spaces.

When examining the visibility gap, exclusion, and social capital challenges female ambassadors face in digital diplomacy, it is apparent that gendered hierarchies persist in these online spaces. Women’s exclusion in diplomacy is structural and digital, requiring strategic interventions to ensure equitable representation in international security.

The Visibility Gap and Digital Diplomacy’s Glass Ceiling

Online bias against female ambassadors stems from a lack of digital visibility, manifested in significantly fewer retweets, lower engagement, and reduced amplification of their posts. Unlike harassment or hostility, this subtle bias censures women in more complex and implicit ways, making it harder to confront. Visibility is a fundamental resource in both diplomacy and media, essential for shaping international discourse and exercising power in the digital age. Without visibility, participation in public diplomacy remains constrained, making engagement on social media platforms a prerequisite for diplomatic influence.

Only ~20% of ambassadors globally are women; this representation gap is further exacerbated by their significantly lower digital visibility than men. X’s engagement dynamics favour male users, exacerbating the digital glass ceiling, with men tending to dominate the most-followed users. Furthermore, women remain underrepresented in the highest engagement tiers due to algorithmic bias. Algorithms that govern content visibility risk perpetuating gender disparities as they often favour content that aligns with prevailing engagement patterns. Algorithms disadvantage female diplomats whose posts historically receive less interaction, as feedback loops (where lower engagement leads to reduced visibility) further diminish the influence of women in diplomatic dialogues.

Although the absence of excessive offensive language and harassment towards women may render the ‘diplomatic Twittersphere’ a ‘safer’ online space for women, it still perpetuates deeply ingrained biases. Unlike overt discrimination, these biases operate implicitly through algorithms, prioritizing male voices. This structural invisibility is more difficult to dismantle because it does not stem from explicit exclusion but rather from the passive reinforcement of existing hierarchies. Women’s contributions to diplomatic conversations are not actively suppressed but are less frequently engaged with, shared, or acknowledged, limiting their opportunities to shape policy discussions and international narratives.

Zoom Diplomacy as Digital Proxy for Traditional Patriarchal Diplomacy

Low visibility and influence patterns extend beyond social media platforms and are apparent in other virtual diplomacy platforms. Even in virtual diplomatic settings, women’s contributions are often overlooked, further reinforcing pre-existing gendered dynamics and hierarchies. Digital Diplomacy, or Zoom Diplomacy, refers to shifting diplomatic negotiations onto video conferencing platforms like Zoom, Webex, and MS Teams. This transition, initially seen as a means of expanding participation, has instead reinforced long-standing gendered power structures. The shift to digital diplomacy was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which quickly revealed new challenges for female diplomats. Digitalization did not dismantle gender barriers but instead reinforced masculine practice.

Diplomacy has historically relied on gender roles and stereotypes. Men typically occupy formal diplomatic roles, forcing women into supporting and submissive positions. Furthermore, diplomatic competence has long been framed through a masculine lens, where qualities like rationality, toughness, and emotional restraint are valued over traits stereotypically associated with femininity. These biases sustain virtual diplomacy misogyny, where men frequently assume women are less adept at managing digital platforms, leading to exclusionary practices like the “let us/me handle this” mentality. Such behaviours reinforce this rigid division of labour that has disproportionately relegated women. Studies on virtual diplomacy additionally confirm that men dominate speaking time and decision-making processes on digital calls, reinforcing these pre-existing hierarchies even in digital spaces. The shift to digital diplomacy has not undone these biases but modernized them, creating new forms of exclusion that mimic past barriers.

In addition to reinforcing gendered hierarchies, digitalization may erode informal advantages female diplomats once had in traditional settings. In face-to-face diplomacy, for instance, femininity is a form of capital that grants women access to high-profile counterparts at diplomatic events or enables them to connect with local communities and civil society actors. These digital platforms significantly reduce these informal networking opportunities and ultimately limit women’s ability to convert social capital into diplomatic influence. Zoom diplomacy thus serves as a proxy for the long-standing institutionalized misogyny that has defined traditional diplomacy.

If Digital Diplomacy Is the Future, Why Does It Still Reflect the Past?

The digitalization of diplomacy replicates traditional patriarchal power structures in diplomacy but in newer, contemporary forms. The transition has further cemented existing gender roles and barriers rather than ensuring equal participation, ultimately thwarting women’s access to high-profile discussions. The persistence of these inequalities across platforms indicates the need to address digital disparities holistically to achieve equitable diplomacy. The lower digital presence of female ambassadors is not simply a reflection of participation rates but a symptom of more profound structural inequalities. If diplomatic influence is increasingly tied to digital presence, the gender gap in engagement and amplification must be actively challenged. Without deliberate interventions, digital diplomacy will continue reinforcing, rather than dismantling, structural inequalities in international relations.

As digital oligarchies consolidate power in the U.S. and DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) initiatives face increasing pushback, the prospects for a more equitable digital diplomacy landscape grow dimmer. If major tech platforms prioritize profit over equity, the same algorithms that suppress marginalized voices today may further entrench gendered and racialized disparities in diplomatic influence, exacerbating the exclusion of women and other underrepresented groups from global governance.

Leave a Reply

The Unrecognized Agency of Women in Latin American Organized Crime

Written by: Abigail Francis

Edited by: Iona Riga

February 28th, 2025

Illustrations of the Latin America’s Most Well Known Women Organized Crime LeadersFeatured Image: Bonello, Deborah. 26 Oct. 2021. International Women’s Media Foundation , https://www.iwmf.org/reporting/las-patronas-the-secret-history-of-latin-americas-female-cartel-bosses/.